There is something vaguely Gothamesque about the name Richmond Penitentiary. It was first mooted when some land was purchased at the time of the development of Richmond Asylum nearby. Both were named after Charles Lennox, 4th Duke of Richmond, who was Lord Lieutenant of Ireland from 1807 – 1816. In one of those nice symmetries Irish history throws up, Richmond went on to become Governor General of British North America, a role later assumed (in the form of Governor General of Canada) by Charles 4th Viscount Monck. Monck’s uncle (and father-in-law, don’t ask) was Henry, 2nd Viscount Monck, later Earl of Rathdown, who originally sold the land for Richmond Penitentiary in the first place.

South of the site of Richmond Penitentiary, Rocque 1757. Stanley St is shown in the south-west corner.

The land for the penitentiary had been occupied by Andrew Quinn, who kept an orchard or some form of market garden. It is clear from Rocque’s plan of the city that the entire area was farmed in some way. Grangegorman Lane, on which the penitentiary was built, is just about discernible on the 1757 map. Channel Row—visible at the bottom of the extract shown—was soon to become Brunswick St, so we can use this as a guide to follow the lane north until it peters out, entering into what must have been Quinn’s plot of 3½ acres. 40 years later, the site was a little more developed, with Grangegorman Lane marked (see map). It’s worth noting here some street names in the area: Stanley Street (visible on Rocque) and Monk (sic) Place (visible on 1798 map). These are obviously connected to the Monck family. Stanley is especially important: Sir Thomas Stanley was a Cromwellian soldier who had the lands at Grangegorman. His daughter and heiress Sarah Stanley married Charles Monck, an ancestor of those we discuss here. Stanley St was once a tree-lined avenue to the Manor of Grangegorman, now it is a lane to a Corporation depot, or a “Scavenging Depot and Destructor”, according to one OSi map.

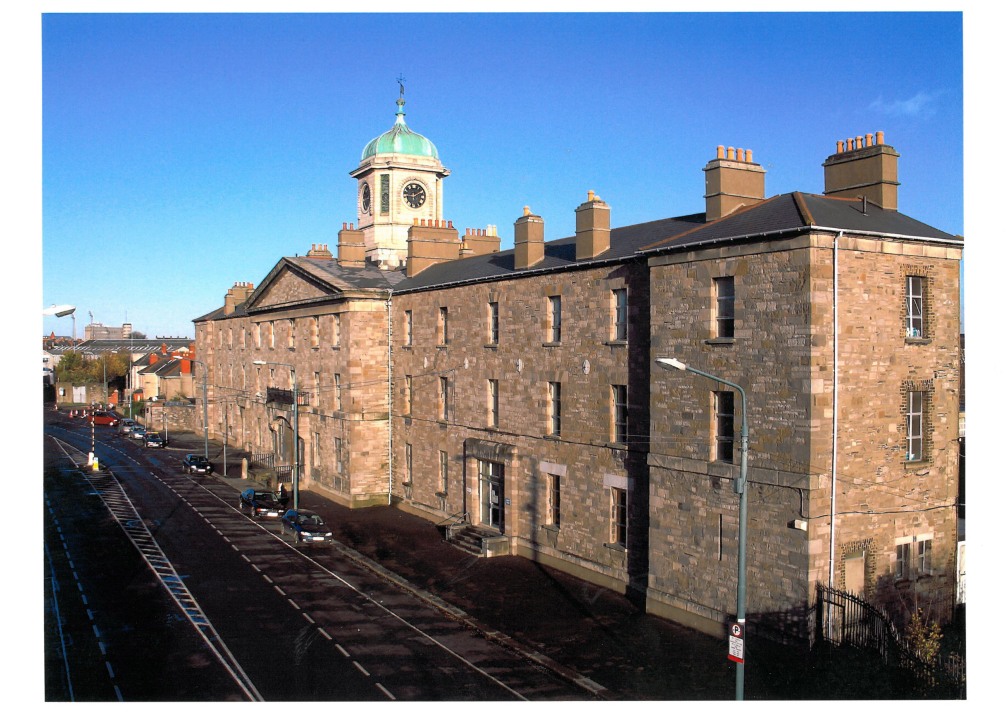

After the sale, Mr Quinn sold his last batch of apples in July 1812, and the wood from the orchard was sold that December. Monck banked £1,100 and a peppercorn (nominal) rent for the land. Francis Johnston was taken on to design the building, having already been employed as the asylum architect. The early nineteenth century was a time when there was a zeal to reform, and rather than send prisoners to far-flung corners of the globe, those with any hope (or potential for Protestantism) were marked for possible redemption and sentenced instead to a local penitentiary, thus the desire for a building in the first place. However, from the time the site was chosen in 1810, it took another decade for the prison to open. The weather vane on the cupola had a date of 1816, and in 1818 the building was used briefly as a fever hospital during a cholera epidemic. The building cost at least £40,000, but was repeatedly criticised for its design (prisons were not part of his repertoire). Johnston’s characteristic “fan” shaped design is visible on the OSi map from the 1830s. Prisoners began their sentence in solitary confinement on the outer confines, and gradually moved towards the centre as their sentence progressed, until they arrived at the workshops at the centre. Each of the cells were 12′ 4 square and 11′ high.

From the outset, the prison was embroiled in the religious debates of the 1820s, similar to those occurring in education, and culminating in Emancipation in 1829. Several boys were transferred from Smithfield in 1821, and the orphans among them were assumed to be Protestant. This was successfully contested by the Roman Catholic chaplain. The tone of the decade in the prison was set. In 1826, the Roman Catholic Archbishop of Dublin, Rev Dr Murray, submitted a memorial on behalf of ten prisoners. The nine men and one woman complained that they had been ill-treated because of their religion, and that proselytism in the form of cruelties, punishments, deprivations and tortures was rife. A 39-day inquiry ensued, which found that while there was mass conversion, torture was not used. Instead, it was ascribed to the “entrance week” that new inmates spent in solitary confinement. After this time, prisoners were asked to state their religion, and it was felt that they may have declared to be Protestant in the hope of an easier time.

Things got worse in the prison after the inquiry. The Roman Catholic chaplain had acted on behalf of the prisoners, so understandably he and the governor were not going to be best of friends afterwards. Conditions in the prison deteriorated and prisoners began to take advantage of low staff morale, and resulting lack of discipline, by committing further “outrages”. At some point it was decided to end the experiment, and just 8 years after it opened, Richmond began to prepare to close. The process took about two years, and the prison closed in 1831. It returned to its former temporary use as a Fever Hospital in time for the Cholera Epidemic of 1832.

References

- H. Heaney (1974) Ireland’s Penitentiary 1820-1831: An Experiment That Failed, Studia Hibernica, 14, 28-39.

- T. K. Moylan (1945) The District of Grangegorman: Part II, Dublin Historical Record, 7(2), 55-68.