And, now after all, let me mention a great discovery that has lately been made for the benefit and good of mankind in general, I mean the Vaccine Inoculation or Cow Pock, which is uniformly mild, inoffensive, free from pain or danger, either in old or young, and an infallible preventative of the small pox, it is never fatal nor yet contagious. The Small Pox has for 12 centuries, been destroying in every year, an immense proportion of the world. [Dublin Time-Piece, 1804]

Outbreaks of small pox in a district could result in fatalities of 20% of the population. It was known that dairymaids were immune due to their exposure to Cow Pox, a much milder disease. After Edward Jenner conducted an experiment where he exposed an eight year old boy to the cow pox pustules on the dairy maid Sarah Nelmes’ hand, and then deliberately exposed him to small pox, he published the results that the boy did not contract small pox, and thus cow pox was an effective vaccination. From the time of its publication in 1798, Jenner’s work became hugely influential in establishing national vaccination programmes. (The word vaccination comes from the Latin for cow, vacca.)

In Dublin, vaccination was available to children of the city in the Dispensary for the Infant Poor soon after Jenner’s publication. Following some extensive vaccination work in Cork, demand in Dublin quickly surged, and in January 1804 the Dublin Cow Pock Institution was opened on North Cope St (now Talbot St) to focus solely on vaccination for small pox. Children of the poor could attend on Tuesdays and Fridays from 11 – 3 pm. Some archives for the Cow Pock Institution are held by the Royal College of Physicians of Ireland, including a subscription book dating from 16th March 1804. The process of securing “cow pock matter” for the purposes of vaccination needed funding, and as well as vaccinating children in the city, packets of fresh lymph were circulated to local dispensaries around the country as part of a nationwide vaccination effort. While vaccination was free for the poor, it otherwise incurred a charge, something which later became contentious. Medical practitioners and other dispensaries could apply to be supplied with packets of infection for half a guinea per annum, and Union Workhouses for a guinea per annum. All post relating to the Cow Pock Institution was free thanks to an agreement with the General Post Office; a letter exists in the National Archives from Dr Hugh Ferguson, apothecary at the Cow-Pock Institution to the government acknowledging the support that is “essential to the existence of their Institution“. The Cow Pock Institution relocated to beside the GPO in the 1860s.

In Dublin, vaccination was available to children of the city in the Dispensary for the Infant Poor soon after Jenner’s publication. Following some extensive vaccination work in Cork, demand in Dublin quickly surged, and in January 1804 the Dublin Cow Pock Institution was opened on North Cope St (now Talbot St) to focus solely on vaccination for small pox. Children of the poor could attend on Tuesdays and Fridays from 11 – 3 pm. Some archives for the Cow Pock Institution are held by the Royal College of Physicians of Ireland, including a subscription book dating from 16th March 1804. The process of securing “cow pock matter” for the purposes of vaccination needed funding, and as well as vaccinating children in the city, packets of fresh lymph were circulated to local dispensaries around the country as part of a nationwide vaccination effort. While vaccination was free for the poor, it otherwise incurred a charge, something which later became contentious. Medical practitioners and other dispensaries could apply to be supplied with packets of infection for half a guinea per annum, and Union Workhouses for a guinea per annum. All post relating to the Cow Pock Institution was free thanks to an agreement with the General Post Office; a letter exists in the National Archives from Dr Hugh Ferguson, apothecary at the Cow-Pock Institution to the government acknowledging the support that is “essential to the existence of their Institution“. The Cow Pock Institution relocated to beside the GPO in the 1860s.

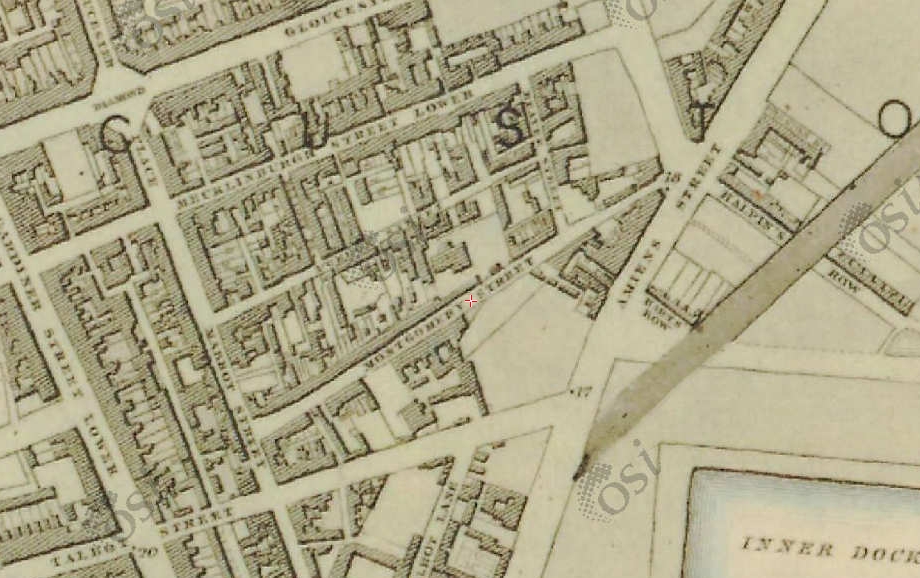

(North) Cope St is hard to pin down. Its southside namesake in Temple Bar still exists, which can confuse searches. (North) Cope St is not on Rocque’s 1756 map of the city, nor Bernard Scalé’s update in 1773, but does appear on the 1798 plan of the city, now running along the north of Marlborough Bowling Green, extending from Earl St. By the time the Ordnance Survey men were mapping the city, a Dispensary is marked in the location, but by this stage it is now Talbot St, named after 2nd Earl Talbot, who was Lord Lieutenant of Ireland from 1817 – 1821. Thus (North) Cope St must be one of the contenders for street names with the shortest lifespan!

Cope St: Top left – Rocque (1756) shows Marlborough Green but no street; top right (1798) shows Cope St running on the north edge of Marlborough Green; bottom OS map (~1840) shows Dispensary marked but now Talbot St; Marlborough Green now gone

Reports of the progress of the Institution were published each year, and in its first year 1000 vaccinations were carried out, rising to 4000 by the end of the decade, along with 3500 packets distributed nationally. Vaccination capacity increased after 1815, when rural dispensaries/hospitals offered vaccination to poor people locally. While the upper and middle classes generally engaged with the vaccination programme – infections among those classes became very low – it was more difficult to engage the working class and the poor. There was an uneasiness about being exposed to vaccination and a lot of misinformation about the dangers of vaccination, captured in a famous satirical cartoon of the time. Repeated publications and statistics were used to reassure the public about the safety and effectiveness of the vaccine, and steadily more people became vaccinated. While there were continued outbreaks – 1500 people died from smallpox in an outbreak Dublin in 1878– their number and extent was much less thanks to ongoing vaccination.

Concern over the safety of vaccination was captured in this satirical cartoon by James Gilray, showing people morphing into cows

The Dublin Cow Pock Institution closed in 1877 when its duties were continued by hospitals. Ireland reported its last case of smallpox in 1907, and the World Health Organisation declared the complete eradication of the disease in 1980.

Updates, as they may come in the future, can be sent to your email address by subscribing below.

Notes

- Elizabeth Malcolm and Greta Jones (1999) Medicine, Disease and the State in Ireland 1650-1940, Cork University Press.

- Samuel B Labatt (1809), “The Cow Pock Institution”, The Belfast Monthly Magazine, 2(8), 183-185.

- Archives area available at the RCPI, NAI, NLI, and the Wellcome Library.