The Mabbot street entrance of nighttown, before which stretches an uncobbled transiding set with skeleton tracks, red and green will-o’-the-wisps and danger signals. Rows of flimsy houses with gaping doors.

Ulysses, James Joyce

In the 1911 Census, the occupation of two Dublin women is entered as prostitute. One was Maggie Boylan living as a boarder on Faithful Place, the other—whose original entry of “unfortunate” was amended by a clerk—was Maud Hamilton on Elliott Place. Both Faithful Place and Elliott Place were off Purdon St, now completely disappeared. At the time of the Census, it was a street running parallel to, and north of, Foley St.

Foley St was called Montgomery St, and this gave the name to the small area just west of Connolly Station that was once one of Europe’s largest red-light districts: the Monto. The Monto came to prominence in the late nineteenth century, and lasted well into the twentieth century, until the new State, prompted by the Legion of Mary, effectively shut it down.

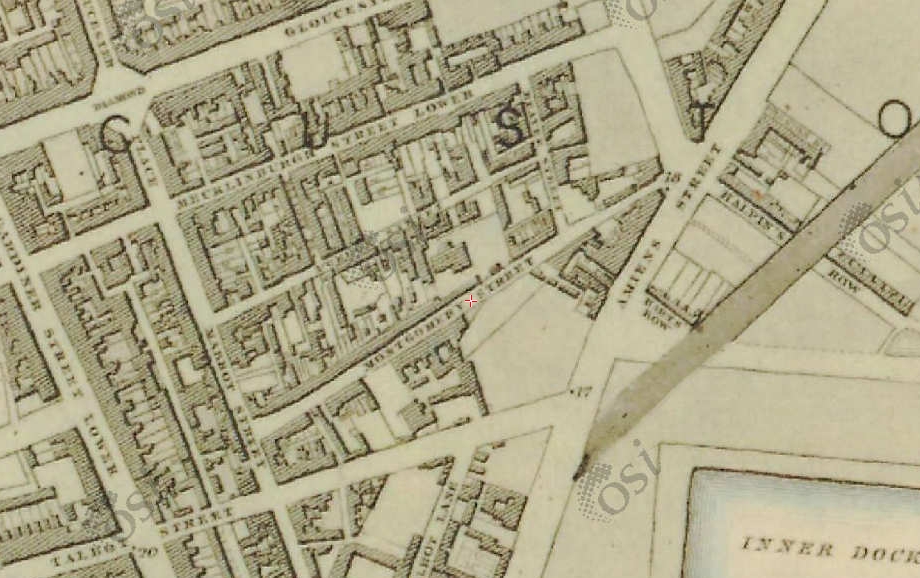

There is no specific boundary for the Monto, but it is considered to be within the boundaries of Gardiner St (to the left/west), Talbot St (to the south), Amiens St (to the east) and Gloucester St to the north. This map ca. 1840 shows many street names before they were changed. The red cross marks Montgomery St.

Oddly, my awareness of the Monto came about through a gift of the book Science and Technology in Nineteenth Century Ireland, which contains an essay by Tadhg O’Keeffe and Patrick Ryan. They write that there is little surviving of the Monto today, with streets, houses, and street names cleared away. They have used the Ordnance Survey maps of the city to trace the growth and decline of prostitution in this small area.

Why did the Monto come about? Early nineteenth century records suggest that prostitution was more prevalent on the south side of the city; with one of the city’s better known Madames, Margaret Leeson, setting up shop in Pitt St, now Balfe St, site of the Westbury Hotel (and the subject of this blog’s first post). In a second essay, O’Keeffe and Ryan propose three reasons why this small part of the north inner city became one of Europe’s most notorious red-light districts. Firstly, the area was far enough from respectable eyes to enable the containment of prostitution away from upper and middle-class residential districts. From the 1870s, there was no shortage of powers available to the police to shut down brothels and arrest their occupants. But they were not used, and the area was openly acknowledged to have ‘open houses’ in a publication of high repute as Encyclopaedia Britannica. Ths is not to say arrests didn’t take place. Luddy reports the Dublin Metropolitan Police records: 2,849 arrests in 1838, 4,784 in 1856; and running at about 1,000 per year from the 1870s. A low of 494 was recorded in 1899.

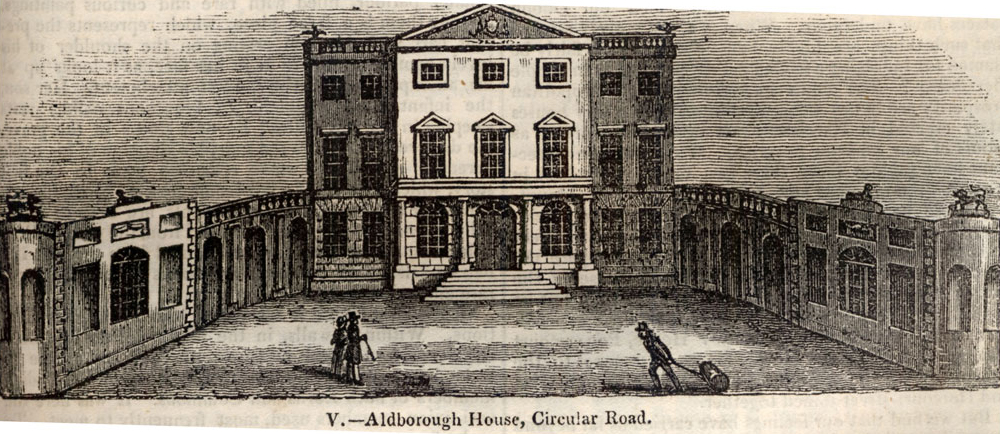

Secondly, the area was a slum, meaning rents were low. And thirdly, and most likely crucially, the area was perfectly positioned next to Amiens St station, Dublin port, and Aldborough House. Amiens St likely provided plenty of young women from the country looking for work. The port and Aldborough house—converted from a school to a military barracks during the period of the Crimean war—provided plenty of clientèle along with the demand of locals.

Elliot Place, 1930s, from the Frank Murphy Collection (Old Dublin Society). Reporduced in Luddy and O’Keeffe and Ryan.

Keeping track of street names in the area is no mean feat. Looking at Rocque’s map from 1756, the area is mostly undeveloped. The extract from Rocque shows Mabbot St running roughly N-S, with “Worlds End Lane” running east-west along what became Montgomery St. O’Keeffe and Ryan suggest that this name indicates that even then, the area “had a long-standing reputation for the darker side of life.”

Rocque’s Map, 1756, showing Worlds End Lane and Great Martin’s Lane, which would become Montgomery St and Mecklinburgh St.

As the area began to be laid out in the mid-Georgian era, Great Martin’s Lane became Mecklinburgh St in 1765. Princess Charlotte of Mecklenburgh had married George III a few years earlier. This street ran through and beyond the Monto’s (loose) boundaries. Residents on the Upper part of the street, describing themselves as “respectable working classes”, lobbied to have the name changed so as to lose the association with the area, and this part of the street became Tyrone St in 1886. But just two years later, the residents in the Lower part had their street name changed to Lower Tyrone St. A medical student walking down Tyrone St in 1904 observed that “in no other European capital have I seen its equal. It was a street of Georgian houses and each one was a brothel”. The Upper and Lower Tyrone streets subsequently became Waterford St and Railway St in 1911, the latter name survives today. Montgomery St had substantial slum clearances in 1905 and the street’s name was changed to Foley St, albeit with the same reputation. Mabbot St—immortalised by Joyce as the entrance to “Nighttown”—is now called James Joyce St. Are you keeping up?

The “other-worldliness” of the Monto, captured by Joyce in his expression of Nighttown is elaborated on by O’Keeffe and Ryan. This area of the city was the inverse of its surroundings; coming to life when Dublin slept, being run by women rather than men; public expressions in the most intimate of places.

While the growth of the Monto may have been due to the turning of the cheek by the law, religious groups were not so unobservant. The all-male and Protestant White Cross Vigilance Association organised patrols from 1885, keeping watch outside “evil houses”. Bizarrely, the neighbours of brothel owners and prostitutes in the Monto were the nuns: the Sisters of Charity, who took over the Magdalen Asylum established on Mecklinburgh St in 1822.But it was the Association of Our Lady of Mercy (Legion of Mary), founded by Frank Duff in 1921 which had the greatest impact on shutting down prostitution in the Monto. Their actions included the persuading of women to leave brothels and take up paid employment elsewhere. The new State’s police force could no longer turn a blind eye and in the Spring of 1925, a large raid resulted in significant numbers of arrests. While this did not shut it down completely, activity petered out over the following years. Street clearances and renamings means that there are no physical marks on the landscape recording this district’s history; the only thing that remains is a white tiled cross on the back of a Magdalen building awaiting demolition and reconstruction.

White tile cross over a gateway on the back of the former Magdalen Laundry on Railway St (Google, 2014)

Notes

Updates, as they may come in the future, can be sent to your email address by subscribing below.

- Tadhg O’Keeffe and Patrick Ryan (2009) At the World’s End: The Lost Landscape of Monto, Dublin’s Notorious Red-light District, Landscapes, I, 21-38.

- Tadhg O’Keeffe and Patrick Ryan (2011) Representing the imagination: a topographical history of Dublin’s Monto from Ordnance Survey maps and related materials, in Science and Technology in Nineteenth Century Ireland, Julia Adelman and Éadaoin Agnew (eds), Four Courts Press: Dublin.

- Maria Luddy (2007) Prostitution and Irish Society: 1800-1940, Cambridge University Press: Cambridge.