Grand Canal Place

at the second hour.

Live lights on oiled water

in the terminus harbor.

Thomas Kinsella, St Catherine’s Clock

Walking around between the Guinness Storehouse and St James’ Hospital, there are some aqueously named streets: Grand Canal Place, Basin View, Basin Lane Upper. Water, water, everywhere. But neither eyes nor satellite show any sight of a drop.

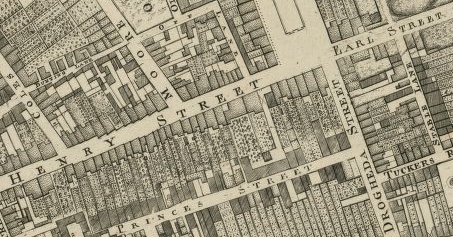

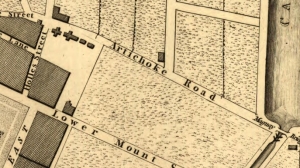

Rocque to the rescue, as always. Tucked away in the south-western corner of his 1756 plan of the city is “City Bason”. The Bason, or Basin was a reservoir supplying this area of the city-especially the ever growing number of breweries and distilleries-with water. It was also a place for local residents to escape the confines of the city’s streets.

With the aid of your monocle, it can be seen that a tree-lined walkway is shown around the basin, and the area was popular as a promenade, so much so that it had already been included as a panel of interest in Brooking’s map of 1728. In addition, it was a venue for musical performances. A concert in aid of the Meath Hospital advertised for August 1756, the date of Rocque’s map, promised a performance of Ellen-a-Roon by Mr Pockrich, playing musical glasses:

Mr. Pockrich hath, (in consideration of so useful a Charity) condescended to exhibit a NEW and CURIOUS Musical Instrument, invented by him very lately, the Effects of which it is impossible to describe, as being entirely different from all either Wind or String Instruments …

It would appear on this particular occasion, that Mr Pockrich’s performance didn’t go well. A subsequent apology appeared from the man himself in the following week’s newspaper: the cause of disappointment was his adding a Glass too much to his instrument.

We digress. The City Basin, Frank Cullen tells us in his fantastic new book was built in 1724, and indeed by the date of the Ordnance Survey map over a century later, the tree lined promenade was still present. A guide to the city in 1835 reported that:

The City Bason is the pleasantest, most elegant and sequestered place of relaxation the citizens can boast of; the reservoir, which in part supplies the city with water, is mounded and terraced all round, and planted with quickset hedges, limes and elms, having beautiful green walks between, in a situation which commands a most satisfactory prospect of a vast extent of fine country to the south. The entrance is elegant, by a lofty iron gate, and the water that supplies it, is conveyed from the neighbouring mountains.

The basin is important for the next part of the story. Its location probably directed the choice of the end of the Grand Canal adjacent to it, completed in 1785. The Canal would serve to keep water flowing to the basin, and hence to the city. (It wasn’t until 1790 that the canal was extended along the South Circular Road to the Liffey.)

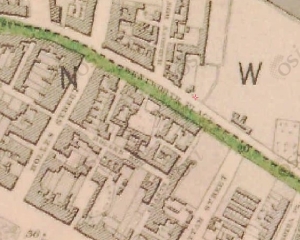

Thus the terminus in the quote from Kinsella above makes sense. Quite an extensive harbour and dry docks are visible in the Ordnance Survey map, and the whole complex meant that this became an important link between Dublin, especially the Liberties and surrounding area, and the rest of the country via the canal. It’s probably no coincidence that the street running east from the harbour, that which now runs along by the entrance of the Guinness Storehouse, is called Market St. Gloriously, a sketch of the area published in the Illustrated London News and reproduced by Cullen gives us a picture of the locality in 1846.

City Basin and Grand Canal Harbour, Illustrated London News, 1846, and reproduced in Cullen (2015). The South Dublin Union Workhouse is visible to the west.

At this time, the area east of the Basin and south of James’ St had not been assimilated into the Guinness empire and one can see (pass the monocle again dear) on both the map and the etching that the area is primarily residential. In this final part, we’ll consider two developments that emerged in the nineteenth century.

Rocque’s 1757 map showing what became known as “Old James’s Gate Chapel” (marked with a cross) on the corner of Watling St, erected 1749.

The first is Echlin St, dominated on the east by St James’ Church. This is the third incarnation of the church; a Chapel of St James was erected by Canon Matthew Kelly in what was known as Jennet’s Yard. This lasted until 1749, when Richard Fitzsimons PP built a church on the corner of Watling St. (Rocque kindly marks a building with a cross at this location.) In August 1852 the present St James’ Church was opened by Dr, later Cardinal Paul. A notice outside the church says that Daniel O’Connell laid the foundation stone. Echlin St links James St with Grand Canal Place. Previously named Echlin Lane, it sourced its title from Rev Henry Echlin, who was the vicar of St James until his death in 1752.

Secondly, the large curved building wrapped around Grand Canal Place is not present on the maps or views of the 1840s. This building, which Cullen describes as warehouses and Casey describes as experimental maltings were built by Guinness in 1863; in either case a convenient location on the water’s edge for distribution nationwide. Facing inwards towards the canal, which like the basin beside it is now filled in, it is the last remnant of the enormous water complex that supported this industrial quarter of the city. One can contemplate Kinsella’s Live lights on oiled water in the Harbour Bar pub just across the road.

You can receive email updates when a new post is published by subscribing below.

Notes

- There is a photo essay of this area on the Irish Waterways History website.

- Brian Boydell (1991) Mr. Pockrich and the Musical Glasses, Dublin Historical Record, 44(2), 25-33.

- Christine Casey (2005) The Buildings of Dublin, Yale University Press.

- Frank Cullen (2015) Dublin 1847: City of the Ordnance Survey, RIA (Dublin).

- Desmond F. Moore (1960) The Guinness Saga, Dublin Historical Record, 16(2), 50-57.