Having served the area since 1891, James’ St post office recently closed and is currently for lease. It was one of several post offices designed by “the always interesting” J. Howard Pentland. Others in Dublin include Ballsbridge, Phibsborough (demolished and rebuilt in 1960), and Blackrock in 1909. Maire Crean’s magnificent book “Lost Post” provides substantial detail on James’ St post office, including the original proposal of the floor plan, now kept in the National Archives.

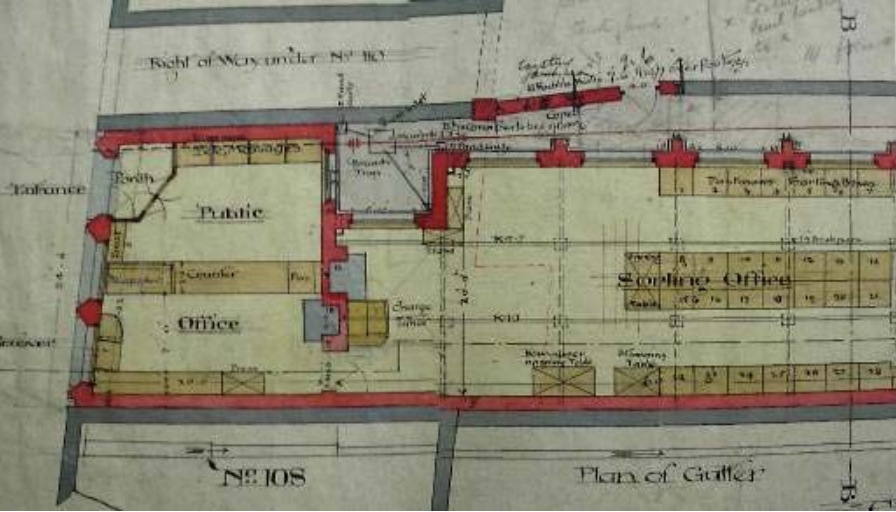

James’s Street Former P.O.; Part Original Ground Floor Plan (National Archives of Ireland, reproduced in Crean).

The public office is visible to the left of the plan, and the sorting office to the right. Crean also treats us to the original elevation – clearly it was originally intended to be a Gothic affair. The door to the public office is on the left on the plans, but from the existing building, we can see it is on the right.

The existing building is part of a trio of red-bricked buildings on the site: two at the pavement, and one in between; a three-storey building recessed from the road. Casey seems doubtful that such a grand building could be for a postmaster, and I can’t find anything in the 1901 Census to counter her opinion. The Post Office in that Census was given number 106, and was of course uninhabited. Using that numbering system, 105 and 104 are the adjoining buildings, and they too were unoccupied in 1901. By 1911, the numbering had shifted to what we currently have: the post office at no. 109, and the large house at 108 was a boarding house for four brewers from England and four domestic servants. 107 remained unoccupied.

Stafford Johnson gained a substantial amount of information from two pieces of paper found in a bin. Most other remaining archives were destroyed.

Postal history can be traced back to James’ St much earlier than 1892. Dublin had an innovative and efficient postal system known as the “Penny Post”, which was established in 1773. The city joined London to be unique in the world with such a system, although according to Stafford Johnson—who has provided us with one of the rare monographs on this topic—Dublin “has some matter for pride in the fact that it maintained the general character of the Penny Post unaltered until the end.”

The Penny Post operated in parallel to the pre-existing General Post system. From 11th October 1773, letters not exceeding four ounces could be delivered from the Penny Post Office in the GPO yard or any of eighteen Receiving Houses around the city, at a cost of one penny. The receiving houses were named in the original correspondence and included Mr. Charles Wren, Hosier, at the Sign of the Stocking, Francis-street near the Combe, Mr. Bredberry, Grocer, at the Sign of the three Swedish Crowns, George’s Quay and Mr. Bourke, Grocer at the Black Boy and Sugar Loaf, Capel-street near Essex-bridge. By 1810, there were 54 receiving houses in the city, and 29 country receiving houses, the extra distance to the country (suburban areas) costing 2 pence.

The original system involved a pre-payment of one penny which was given in to the Penny Post Office or receiving houses. Letters that did not have the accompanying penny were opened and returned to the sender. A plea was made to be as precise as possible with the address, and those intended for lodgers were to name the landlord or the sign (on the building) to assist the post men.These men wore a distinctive uniform from 1810, and like their colleagues in the General Post system, rang a bell when on collection duty.

In 1810, the pre-payment system was abandoned. The official reason isn’t known, but Stafford Johnson offers with some confidence his theory that pre-payment ran counter to the public sentiments of the time. Payment on delivery would be preferred as it secured a safer delivery, and poorer people could take advantage of the system by refusing to accept delivery (and hence avoid the charge) while learning who the letter was from. Apparently secret codes were used so that the recipient could interpret the message with accepting the letter. Nonetheless, the system was a successful and efficient means of communication in the city. The post-masters general were eager to highlight the benefit of their system and regularly published the notice:

So expeditious and regular is the dispatch and delivery of letters by this Office that two persons residing in the most distant parts of the City from each other, may write four letters and receive three answers in the day for the trifling expense of one penny on each.

Back at James’ St, a receiving house opened on the street in 1809/10, and we can propose that this house is a precursor to the post office mentioned at the head of the article. The listing of a receiving house at No. 75 in the 1862 street directory adds some weight to this proposal. Here, William Madden, M.D. operated his medical practice, and acted as a Post Office Receiver. In addition to the house on James’ St, a second receiving house opened on Echlin Lane (now Echlin St) after 1810. The latter joined receiving houses at Broadstone Hotel and Portobello Hotel linking the city system with the Royal and Grand canal harbours (see In the fields off James’ St).

The Penny Post system ended in 1840, because of a combination of factors, not least the duplication with the General Post system. Stafford Johnson closes his article with the following:

Looked at as a whole, the Penny Post was worthy of the City and fulfilled its functions truly and well. For 66 years it gave a service which for cheapness and quickness has never been equalled. All this was done by men on foot, and to-day, in spite of the advantages of modern science, there is nothing to come up to that old system of which all that remains is a memory and some faded old letters.

You can receive email updates when a new post is published by subscribing below.

Notes

- Christine Casey (2005) The Buildings of Dublin, Yale University Press.

- Maire Crean (2012) Lost Post : A Selection of Ireland’s Post Office Buildings. See also Dublin Institute of Technology repository for Crean’s thesis on this topic.

- J. Stafford Johnson (1942) The Dublin Penny Post: 1773-1840, Dublin Historical Record, 4(3), 81-95.