In the shadow of Saint Nicholas of Myra,

Where salt waits, oil in its cruse.

You will find your own way out of this maze.

Harry Clifton, A Son! A Son!

In the Protestant parish of St Nicholas Without, a small complex of schools existed on New St, a short street linking what is now Clanbrassil and Patrick Sts. The early Ordnance Survey map marks the school’s location and Sir John Gilbert lists details of schools in the city, most likely gathered from one of the many, many Irish Education Inquiries the Government established to try to decide what to do with education provision. He states that the school on New St had a yard and playground that was spacious. This was not common – compare, for example with St Nicholas Within, which had no yard, and a “dirt hole and necessary” on the ground floor. The school had dormitories which were airy and clean, but the school room itself was “small, dark, and inconvenient”. There were 20 boys boarding; the parish had a population of over 12,000 at the time.

We can trace the school pretty easily using street directories. By 1834, there were Male, Female, and Infant Schools on the site, with the children taught by James Farrell, Miss Moore, and Miss Macnamara. By 1842, the male and female schools were run by Jenkinson Hudson and his wife. Now I should say that Jenkinson is something of an old friend, as he cropped up in my study of Wicklow schoolhouses during the Georgian era. There we find him teaching in a school in Calary, aged 20 in 1823. Calary is as remote as you get in Wicklow, on upper plains between Kilmanacogue and Roundwood. It must have been quite a change for him and his wife to move to the city. Jenkinson was replaced at Calary by John Nelson Darby, so it is likely that he conformed with the evangelical ethos of that school, and perhaps this made him a suitable candidate for the school at New Street. This is further confirmed by the fact that while the school received support from the (secular) Kildare Place Society, it was not formally associated with it (see An Education at Kildare Place). Jenkinson had received training from the Society in 1823.

A little walk

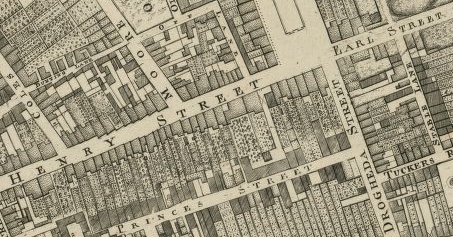

Of course, following the relaxation of penal laws in 1785, most Catholic children were openly educated by Catholics, either in hedge and pay schools, or schools established on church lands. A short walk away from New St, the Roman Catholic schools for the parish were on Francis St. This walk is different today, with New St leading directly onto Patrick St. Then, a Wide Street Commissioners map informs us, New St fed into Kevin St, with a small alley named Three Stone Alley linking New St with Patrick St. The triangle now occupied by a large junction and abandoned subterranean toilets was once a compact cluster of houses.

Three Stone Alley, linking Patrick St to New St (from Dublin City Library collection – click to go to source)

On Francis St

St Nicholas of Myra Roman Catholic Church was built in the years following Emancipation in 1829. While there is a substantial amount of information on the church, very little appears to exist on the schools that were built on the church grounds. We know of the existence of these schools from the Ordnance Survey map which shows that by the end of the nineteenth century, at least two schools were present just north of the church.

The provision of education in early nineteenth century Ireland resembled a chaotic auction where various religious societies tried to outbid each other offering support to nascent schoolhouses. Support came with the obligations that a school would operate under the moral guidelines of a particular society, use their textbooks, and crucially, follow their interpretation of the Bible. Amid this chaos, the Kildare Place Society emerged, and became the major supporter of secular education in Ireland (see An Education at Kildare Place). The Society was formed in 1811, and from the 1820s, was the dominant Irish educational society, receiving £30,000 from Government to support schools.However, the Kildare Place Society was under attack from the Catholic bishops, and after a Parliamentary Inquiry in 1826 and Emancipation in 1829, the money previously directed to Kildare Place was used to establish the Board of National Education in 1831. Ireland had a National School system.

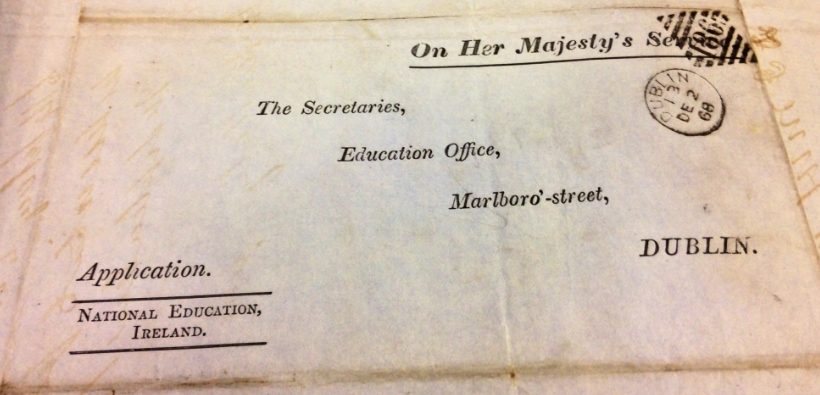

The Commissioners of Education offices and Training School were at Malboro’ Street (National Archives of Ireland)

Having petitioned for its formation, the Roman Catholic church quickly began to associate schools it currently supported as well as new schools with the National Board. This involved applying to be connected with the Board, through support of teacher salary, request for desks, books, etc. These applications are now kept in the National Archives of Ireland, and they are a rich source of information on localities. The earliest record for St Nicholas Without is an application in 1842 for a Female School. In this, the correspondent Fr Matthew Flanagan reported that the school house, consisting of two rooms, each thirty by forty feet, had just been completed, having been built by private subscription. Later documents make it clear that this building was in fact a school for boys and girls, with a room for each. The application was approved, and the school became popular. An application for further assistant in 1868, from Fr E McCabe, requested a salary for Eliza Saunders, aged 18. Her qualifications included a “Certificate of Professors”. She would join Mary Ledwidge, principal teacher, Julia Shalvey, Margaret Dowling, Kate Macken and M. A. Shalvey (both junior monitors). There were at that time 190 boys and 190 girls on the rolls, with average attendance of 116 boys and 116 girls.

Application for St Nicholas Without Infant School Assistant Teacher Salary, 1862 (National Archives of Ireland)

The complex grew, and as well as girls and boys, the parish applied for assistance with an infant schoolhouse in 1853. The application by Fr Flanagan requested money for payment of teacher’s salary and for supply of books. He stated that the schoolhouse was newly built, with brick and slate in the cottage style, 65 feet long and 18 feet wide, standing close to the church on Francis St. It was furnished with a gallery and capable of accommodating 170 children, who were taught by Elizabeth Murphy, aged 44. Daily hours were 10 to 3, with hours devoted to religious instruction 12 to 12.30. Books used were those of the National Board. A salary of £10 was granted to Elizabeth and books for 150 children provided.Again this school was successful.Several applications for further assistance followed; within a decade there were 234 boys and 131 girls on the roll, with an average daily attendance of 138 boys and 60 girls.

While the Roman Catholic schools of the parish embraced the National School system, there is no record of the schools at New Street joining the system.Initially schools with a Protestant ethos were reluctant to join the National School system, and they continued with the support of the Kildare Place Society, which later became the Church Education Society. However, by the 1850s, money began to run out, and schools tended to drift into the National system. It is likely therefore that in the absence of any application, the schools at New Street closed.

While the Roman Catholic schools of the parish embraced the National School system, there is no record of the schools at New Street joining the system.Initially schools with a Protestant ethos were reluctant to join the National School system, and they continued with the support of the Kildare Place Society, which later became the Church Education Society. However, by the 1850s, money began to run out, and schools tended to drift into the National system. It is likely therefore that in the absence of any application, the schools at New Street closed.

Roman Catholic schools clearly continued on with some success, and in the 1930s, a new schoolhouse was built at Carman’s Hall, a narrow lane linking Meath and Francis Streets, just in front of St Nicholas of Myra church. Casey describes it as a simple modernist building by Robinson and Keefe, with statues of the Virgin, St Nicholas, and original Irish signage. Like its predecessors, it is now closed. The footprint of the schools around the church at Francis St is now occupied by a modern building housing Francis St CBS.

You can receive email updates when a new post is published by subscribing below.

Notes

Notes

- The records of the National Board of Education are available in the National Archives of Ireland. There is a card index. The files accessed for this article included: ED1-29-136, ED1-29-118, ED1-29-1. Those eager to follow up the schools’ histories are encouraged to examine the ED2 records.

- A contemporary image of the intended elevation of St Nicholas of Myra Church is available in Dublin Penny Journal, reproduced at Dublin City Library. Meanwhile, I enjoyed this letter from Sgt. Brace in 1977 to The Irish Times…

- Christine Casey (2005) The Buildings of Dublin, Yale University Press.

- Michael Seery, Education in Wicklow; From Parish Schools to National Schools, 2014.This book is free to read on Google Books.