While it is perhaps not surprising that cities such as London, Birmingham and Liverpool saw a surge in Welsh chapels – chapels where the faithful could worship in Welsh – I was surprised to learn that a Welsh Methodist chapel was built in Dublin in 1838. The intended congregation were mostly sailors from Holyhead, with the intention that encouragement to spend an hour in prayer was an hour less in the public house. Other members of the congregation drew from the 300 Welsh soldiers billeted in the city, patients coming on the boat from Holyhead for treatment at the Adelaide Hospital, and Welsh people who had taken up residence in the city to work as maids, nurses, and other professionals. Encouraged or not, before the chapel was built, those wishing to worship in Welsh had to use a Dutch Lutheran chapel on Poolbeg St, although all collections had to go to “the Dutch”.

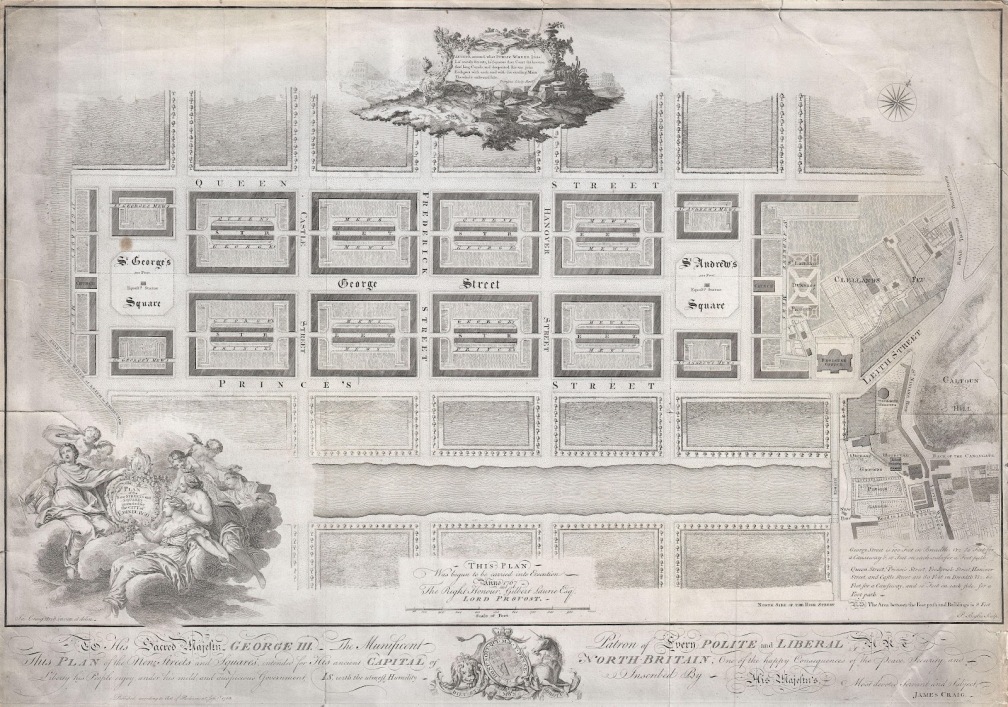

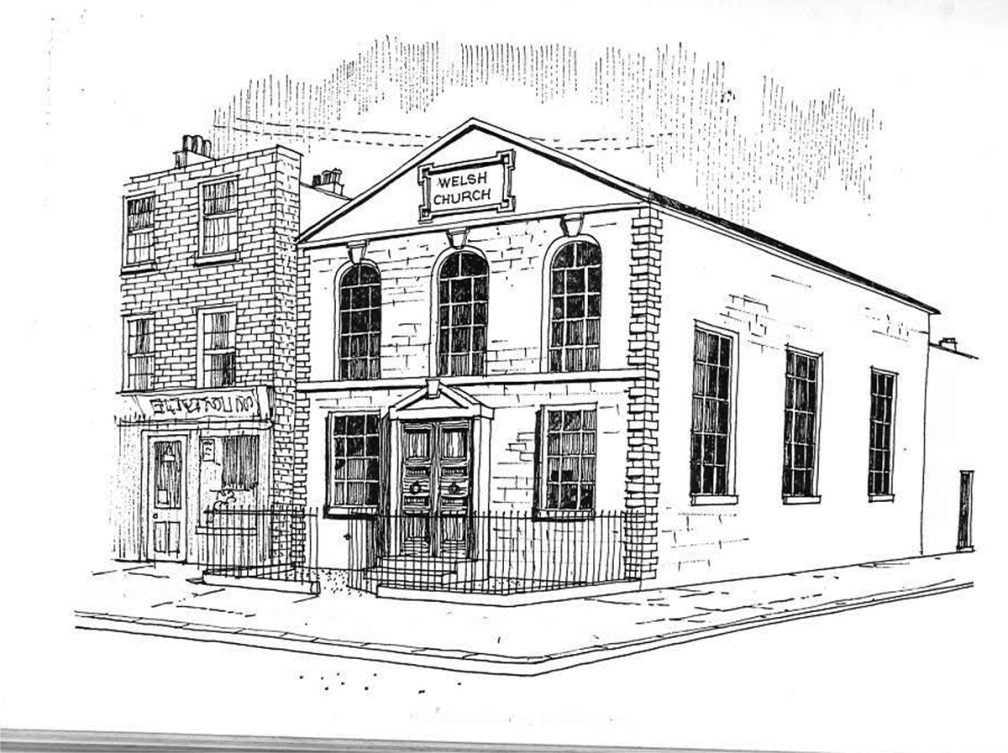

Capel Bethel, as illustrated in Wrth Angor yn Nulyn (Caernarfon, 1968) © Gwasg y Bwthyn, Caernarfon, taken from Roberts (2018)

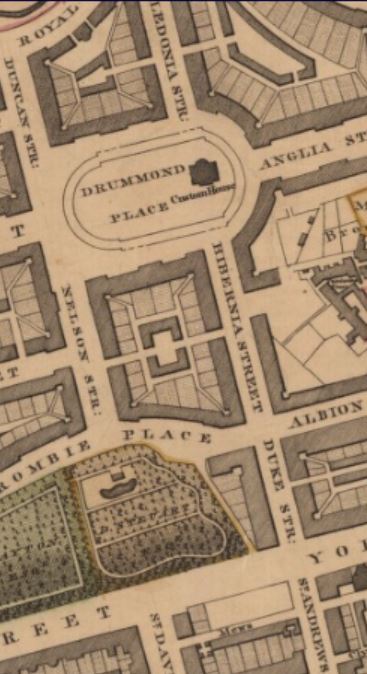

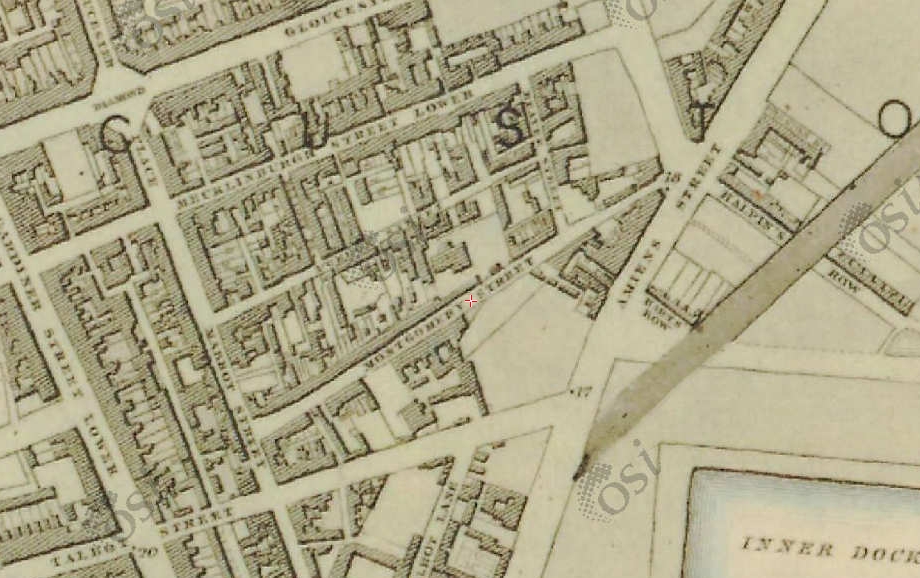

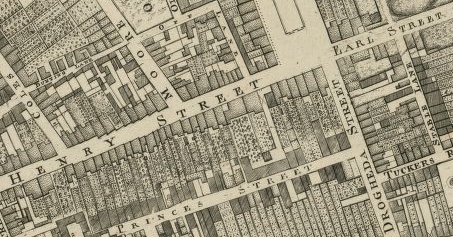

The chapel’s foundation stone was laid in 1838 on land secured by John Roberts, a Holyhead business man, thanks mostly to the efforts of the first pastor, Rev Robert Williams. The church was named “Bethel Church”. It was 40 ft x 27 ft, built of brick and cornerstone of Whitland granite from south-west Wales, at a cost of £500. The chapel appears to be just too late for noting on the OSi map of about 1840, but does appear in the 1842 Pettigrew and Oulton’s Directory and in the 25” maps from later in the century. The 1862 City Street guide proclaims a “WELCH METHODIST PREACHING HO.” at the junction between Talbot and Lower Gardiner Streets, with the chaplain named as Rev. Evan Lloyd. Lloyd was a popular preacher but perhaps more than that; another city chaplain remarked that he was “the father of all the Welsh girls in Dublin”!

The chapel’s capacity was reported to be regularly full in the 1840s, and with the onset of railway and ferries, capacity of 300 needed to be expanded in the 1860s, when a new gallery added 60 more spaces (nicknamed the quarterdeck by maritime patrons). In fact only sailors were allowed on this quarterdeck, and an account of a captain visiting with his wife is reported, with the good lady being told on seeking to enter the gallery: “main deck for you my girl!”. Further building work in 1894 was supported by money from Methodists across Wales, a ‘Wesleyan nobleman’, as well as a member of the Moravian cause, and “even received help from the Papists”.

In the 1901 Census, the chaplain John Lewis is recorded aged 42, and living at 77 Talbot St with his wife Elizabeth and their one year old Alun. 10 years later they were joined by a daughter, Olwen, and were living behind the church in Moland Place. John was by all accounts a character, and was known as the “Welsh bishop”, wearing a wide, flat hat on his missions around the city. The hat reportedly took a bullet in the Civil War.

William Griffith’s Shoes and Ladies’ Fashions. Photo: 1968. © Gwasg y Bwthyn, Caernarfon. Taken from Roberts (2018). The house on Moland Place is just visible behind the church.

However declining congregation meant that the Church’s days were numbered. It was likely that it was severely damaged in the War of Independence; the National Archives are full of requests for compensation for building damage in this area during the War, including one from William Griffith a boot merchant, at 78 Talbot St. There was an explosion outside Moran’s Hotel in July 1922, and several houses and businesses on the street claimed compensation.

Griffith the bootmaker comes back into our story when the church finally closed in 1938. He took over the building and had a shop there. The doorway moved to the corner and tiling added advertising “Griffiths”, still there to this day. The building was last used as an internet café, looking seriously worse for the wear, but thanks to the effort of the Welsh Society in Ireland is now on Dublin City Council’s protected structure list. They are petitioning for a plaque.

A clip from the RTÉ programme Capital D, including a remarkable interview with the 103 year old Howell Evans is available on YouTube at this link: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cpFHYO-DNZ4

Updates, as they may come in the future, can be sent to your email address by subscribing below.

Image from Google Street View (2018). The tiling, announcing “Griffith’s” is visible at the entranceway

Notes

- Evans, H. (1981). A Short History of Dublin’s Welsh Church, 1831 – 1939, available at the Welsh Society in Ireland’s website: http://www.welshsociety.ie/features/

- McLean, E. (2013). The extent of Welshness amongst the exiled Welsh living in England, Scotland and Ireland, University of Wales Trinity Saint David, page 36.

- Roberts, D. (2018). ‘Two hands over two sands’: Capel Bethel, Dulyn: the Welsh chapel in Dublin. Folk Life, 56(2), 65-76.